Hello, Mama, HaPpY Mother’s Day!

Olga Wright grew up in the city of Jackson, Mississippi, the middle sibling of six brothers and one sister, with an imposing father who founded one of the largest and most respected funeral homes in the South—Wright & Ferguson Funeral Home. A man who in his 80+ years of life never needed false teeth because he brushed twice a day.

As a young girl, Mama was taught to be a “genuine Lady.” And she never wavered.

Never once did I, or anyone I know of, witness anything haughty about her—not toward household help, farm laborers, their wives, or even the local town drunk. She had a heart of gold. And the looks to go with it.

With a personality that beamed and morals that never wavered I suppose that’s why she was respected and adored by both genders. At Millsaps College she was a Homecoming Queen, a majorette and a ‘favorite’ on campus. Many days after school, she’d model for Kennington’s—the “Saks 5th Avenue” of Mississippi.

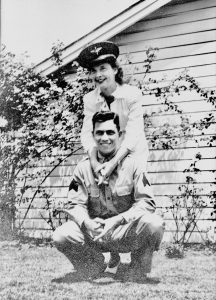

Surprisingly, her strict parents offered to pay her way to New York if she truly wanted to become a serious model. But love intervened when she met a dashing WWII pilot—a twenty-two-year old Yazoo County farm boy who eyed her across the dance floor in Jackson one summer and announced to his friend, “See that girl? I’m going to marry her one day.” And he did.

Surprisingly, her strict parents offered to pay her way to New York if she truly wanted to become a serious model. But love intervened when she met a dashing WWII pilot—a twenty-two-year old Yazoo County farm boy who eyed her across the dance floor in Jackson one summer and announced to his friend, “See that girl? I’m going to marry her one day.” And he did.

Mama never made it to the Big Apple. She became a farm bride. Only by God’s grace did she adapt—and adapt she did.

She raised four strapping boys on a small farm, in a tiny farmhouse. This was no plantation and certainly no plantation farmhouse. Think 1,400 square feet, on a hill with an acre of open, sloping front yard with a small pond below (where our local Black church would bring their white-robbed members for Baptisms.)

At sunrise I often went with Mama to the chicken coop to gather fresh eggs for breakfast. A dozen laying hens took up residence in the coop with one outside rooster, which she kept confined until the egg supply slowed. There were other chickens, called yard chickens, but they had another purpose in life.

For me, the egg came first, not the chicken. The small coop was an old wooden shed about ten-by-ten with layers of hen boxes on both sides.

The early easterly sun filtered through slats in the walls, producing thin rays of dusty, particle-filled light making the air sparkle with tiny feathers and pixy dust. I remember it to this day. She’d stroll through the coop, shooing hens off their nests, snatching an egg here and there to fill her wicker basket.

Thirty minutes later, in the kitchen, four boys and one farmer sat down to a passel of sunny-side-up fried eggs, bacon, grits, and cornbread pones. Nothing better.

She taught us to use the end of a spoon, dig a hole way down in the end of the pone, fill it with sugarcane molasses, hold it up, and eat it from top to bottom.

We never ran out of molasses. Every year, she and Daddy would supervise the mule, harnessed to a screw press, circling the concrete vat filled with sugar cane stalks. We’d stand around and watch the elixir get squeezed out through a spigot into a trough at the bottom. The juice would be cooked down into a thick cane molasses and stored in one-gallon cans.

At Christmas time farm laborers and neighbors down the road were presented an annual supply of the world’s best sugarcane molasses.

One afternoon, in amazement, I watched Mama chase down one of those yard chickens, ring its neck, pluck it, cut it into parts, wash it, dust it with her cornmeal recipe, then fry it in her prized cast iron skillet. Supper! The yard chicken’s purpose in life.

I don’t believe her siblings ever did that.

She had her own flock of sheep, which were sheared for wool, then sold. Not the sheep—just the wool. We didn’t need the money so much as she knew a sheep should be sheered once a year. Like a good shepherd she cared for those sheep and felt compelled to protect every last one of ’em. With no slingshot handy, she learned to shoot wild dogs and coyotes at a hundred paces using an old .22 caliber rifle. I’m not exaggerating.

I don’t remember her ever mentioning a lost sheep or letting Daddy cook one for a feast. Although I do wonder where our fine taste for lamb came from. “Duh, Mama, did you ever let Daddy harvest one or two? You’ve always been honest as sunrise, and now that you’re in heaven, you have no choice but to be completely honest, right? Send me your answer, please.”

Using Butterwick mail order patterns, she sewed many of her own dresses. Probably used the same scissors to cut our hair, but at that age I didn’t care if she used a bowl cut or not. Besides, we lived too far out in the woop woop to visit any bona fide barber. BTW, she gave birth to two of us in her own bed. Dr. Jesse James showed up after the fact, smoking a cigar, just saying how brave she was. I remember everything.

The oldest two boys were born in Monroe, Louisiana in an Army hospital. Daddy was a pilot stationed there during the big war. Good thing he wasn’t shot. But Mama was.

One day a bird fluttered into the house, banging on walls, the ceiling, wreaking havoc. Our oldest brother gathered the rifle and fired at the highly agitated bird. The bullet ricocheted through a door and went clean through Mama’s right calf.

That didn’t bother her as much as the day we four boys tipped over a can of molasses, stomped around in it, then ran through the house, screaming, thinking what fun it was. That was the day she could have and should have become a child killer.

We think she kept her sanity by allowing us to pack some PB&Js in our saddle bags, hitch our horses and be gone all day on our own adventures and imaginations in the woods and the giant gulley on the property. It’s where we played cowboys and Indians and didn’t come home ’til we heard the dinner bell, just like Little House on the Prairie.

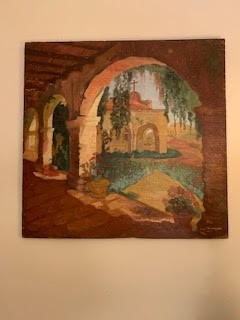

For more sanity she took up painting. Her first effort in 1950 wasn’t too bad. She bought oils and painted a Mexican church scene from a magazine photo onto a salvaged four-by-four piece of plywood. She soon started painting people and sculpting. Natalie in the neighborhood posed for her and darn if the result wasn’t the spittin’ image of her.

Daddy built Mama a brick kiln in the back yard. She used a foot pedal wheel to mold her wet clay and create her art and pottery. Lots of it.

When Great Aunt Florine Hicks Puffer died in 1955, we left the little house on the hill and moved into Bentonia, population approximately 300, maybe 400. Auntie and Daddy’s mother, Eloise Hicks Thompson (who lived in Jackson), inherited Egypt, the name of the place Daddy farmed. To this day nobody knows why it was named Egypt. There was certainly no comparison in size.

Anyway, Auntie’s casket had been on display in the bay window of the dining room for two entire days. I was five and peeked in the open casket once. It was my first and last encounter with pale skin and pink rouge. There was no need for me to look again. Then they buried her.

When Mama wasn’t planting new bushes or spinning her potter’s wheel, she was helping us shuck oysters in the back yard, next to Daddy’s office, which doubled as his poker playing casino with his farmer friends. (Winters were boring.)

It was Daddy who taught us to shuck and suck. No cocktail sauce. No catsup and horseradish. No nothing. Just shuck and suck. That’s the way we learned to love ’em. Mama, too. Then one day her oyster knife slipped off a stubborn oyster and went clean through the flesh between her thumb and index finger. Stitches and a tetanus shot followed. But no tears or complaints.

By the time I was eight Daddy took us boys to Vicksburg and bought a 15-foot ski boat which he named Lady O. It was christened on Wolf Lake, north of Yazoo City. He built a wooden pontoon boat and welded 55-gallon drums together for flotation. That was our temporary home away from home. Every Saturday in the summer Mama would make a thousand pimento cheese sandwiches, pack enough Coca-Colas in ice chests to sink the Titanic and we’d trailer the boat forty-five miles to the pontoon which remained tied up to a tree on the lake. Nobody ever stole it. Wolf Lake is where Mama became a graceful slalom skier. She loved it.

But one Saturday, in the high school and college years, we went to ski with a bunch of friends and no adult supervision. We were all sunbathing on the pontoon’s top deck. By mid-afternoon a show-off skier came too close and slammed into the pontoon. We all ran to the edge to look down. The entire pontoon tipped over. Ice chests of beer, food, towels and all went floating. We couldn’t believe our eyes when the pontoon popped back up without a hitch.

Plenty more could be written about Mama, and how she made a major life-changing adaptation from city girl to farm girl. But her most memorable contribution for us? She prayed every day for her four boys’ salvation for forty-six years of her life—since the oldest was born till the day she died at age sixty-seven in 1987. Growing up, she made sure we were in church every Sunday—spit shined and all. She cared how we presented ourselves.

Thank you, Mama. God answered your prayers. All of your boys eventually became God’s children. Your prayers had to be some kind of powerful for God to allow us a name in His Lamb’s Book of Life. Thank you!

Now, lest somebody think I’m a Mama’s boy—a sissy—I should let you know I’m anything but. I have the scars to prove it—twenty-four broken bones, eight alone from one Harley massage. Twenty-three fist fights (not necessarily associated with the broken bones). At least a half dozen car wrecks. A night in jail. And much more than I’m willing to confess here.

Mama was kept insulated from most of our brotherly shenanigans, but I suspect she knew anyway. Maybe it’s why she prayed so hard and successfully for us.

Maybe I’ll write about Daddy for Father’s Day. Whew. That’d be a story. What a man! A reluctant farmer who drank and gambled too much; but sweet when sober. He died far too young at fifty-seven from a heart attack. We all wished we could’ve known him better. He reminded me of Humphrey Bogart, without the gangster persona.

Thank you, Mama. Your four boys know life would have been a lot different without you. You have wings.

Michael Hicks Thompson, written hopefully with the same sentiments as Frazier Robinson Thompson, III; William Puffer Thompson, MD; and Walter Wright Thompson, Esq.—the four brothers.

What a wonderful tribute to your mother. I am honored to be named for her.

I just found this. Tears welled up as I read it.Thank you for a great tribute. You mom was as close to a surrogate mother as I could have had and I have thanked God for her influence in my life. My mother considered her a sister, best friend and confidant. To me she was bigger than life in her most basic duties as a homemaker in Bentonia. A hero to me in my art interests. A legend in the community for her emergency midwife efforts. But most of all, a deciple of Christ and tireless example for all of us. No doubt she had her faults, but as honestly as I can look back, I can’t remember any. Her efforts are exemplified in her children. This tribute will be cherished and passed on to my grandchildren.

I loved reading about your mother! What a childhood you had. I was a northern city girl and your southern childhood seems magical to me

Finally getting around to emails! I loved the article about Mama T. And please write one on PaPa! I am honored, as well, and love my namesake and her name. Thanks for sharing your memories of Mama T! I am so thankful of my memories of Bentonia and Egypt and can envision every place and scene you mentioned in the article. I remember the Bentonia house like it was mine. The pool, the feast and decorations at holidays, the upstairs 4 twin beds in corners, their master bedroom being so tall and elegant with the bed and tall ceilings. I remember the bathroom Papa died in right next to the bedroom! I remember running through the kitchen and around the white table with PaPa sitting right there in the kitchen. I remember being so excited to go to visit Mama T. and Papa. I was 6 when PaPa died but remember him so well! One of my most vidid memories was when I was running around the house, running in circles around the white table, and I got thirsty. I just grabbed a cup filled with what I thought was CokeCola, but, as I gulped it down, ended up being a cold brew of coffee! I despise cold brews to this day because of that memory!